The "High Water" mark of the Confederacy has crept

into and has remained as part of the historiography of the Battle of Gettysburg

ever since "Colonel" John B.

Bachelder experienced an awakening as he strolled The Angle area of the Union

line on Cemetery Ridge during the 1880s.

As Superintendent of Tablets and Legends for the Gettysburg Battlefield

Memorial Association, he supposedly coined that phrase to describe the ineffective

Confederate breakthrough near a thicket

of trees.

This point may well reflect the greatest point of incursion into

the Union defenses by the Pickett-Pettigrew-Trimble charge during the third day

of battle. Is the high water mark label

accurate when one views the entire campaign?

Geographically speaking the stain of the high water mark was left behind

in Cumberland and York Counties which represents the furthest points north and

east attained by the Army of Northern Virginia (ANV).

The second foray into the North by Confederate General

Robert E. Lee became known as the Gettysburg Campaign which many historians say

began on June 3 and ended on July 14, 1863.

The label Gettysburg is used because the largest land battle in North

America occurred in the borough of Gettysburg and surrounding area during the

campaign. June 3 represents the date the

ANV starting moving north and July 14 is the date the ANV crossed the Potomac

River in retreat from its sortie.

Lee had several reasons for venturing north which included

relieving Virginia of constant warfare, gathering supplies such as livestock,

feed and food from the northern states as yet untouched by war, to engender

support from the northern antiwar faction called Copperheads and of course

destroy as much of the Union Army of the Potomac as possible.

To alert and panic the northerners Lee determined his focus

would be on wreaking havoc in the north by menacing cities such as Harrisburg,

Philadelphia and Baltimore. He wanted to

frighten the politicians in Washington to a degree that with adequate public

pressure, the federal government would sue for peace.

|

| Plaque on the Governor Curtin statue in Harrisburg |

|

| State historical marker in Harrisburg. |

General Richard Ewell commanding the Second Corps of the ANV

was the lead element of the ANV which crossed the Potomac River on June 15. On that same day orders were sent to Ewell from

General Lee concerning his mission in Pennsylvania which included the

following, "If Harrisburg comes

within your means, capture it."

On June 25 in Chambersburg, General Ewell met with General

Early, one of his division commanders. General Ewell ordered General Early to cross

South Mountain and go through Gettysburg.

He was then to proceed to York and cut the Northern Central Railroad

which ran from Baltimore to Harrisburg.

Early was also ordered to destroy the Columbia-Wrightsville Bridge which

carried track from York to the Pennsylvania Railroad at Columbia.

On June 26 Early's column easily traversed Adams County, staving

off some militia units and while in Gettysburg he garnered some supplies and

rations. Part of Early's column

commanded by General Gordon took York on the 28th without opposition. Early had ordered Colonel White's battalion

of cavalry to ride to Hanover Junction and destroy as much track and bridges he

could of the Northern Central.

Upon Gordon's arrival at the Wrightsville Bridge he found it

was defended by 1,200 militiamen. Shortly

after Gordon attacked the defended portion of the bridge, the militiamen began retreating

across the bridge. The defenders outran

the Confederates and fired the bridge in the process. The bridge was totally destroyed and it

actually ignited several buildings in Wrightsville. The Southerners quickly transformed

themselves into firemen and assisted the locals in quenching the flames.

With the bridge burned and unusable, Gordon and his men remained on the west bank of the Susquehanna River. Harrisburg was safe, for now.

General Ewell continued north up the Cumberland Valley with his other infantry divisions

commanded by Generals Rodes and Johnson and a brigade of cavalry lead by

General Jenkins. Jenkins brigade was in

the lead and it was his duty to perform reconnaissance for the infantry corps.

Most of the Union troops Ewell encountered in Pennsylvania

were not from regular army units. These

troops mustered to defend against the invasion into the state were militia and

emergency troops from Pennsylvania, national guard units from New York State and even some troops from New Jersey. Locally recruited colored troops were used as well.

emergency troops from Pennsylvania, national guard units from New York State and even some troops from New Jersey. Locally recruited colored troops were used as well.

After easily brushing off some skirmishers at Stones Tavern

in Cumberland County, Jenkins occupied Carlisle, the county seat and location

of the U. S. Army's Carlisle barracks.

The handful of Union defenders wisely retreated north rather than take

on the 1,200 troopers of Jenkins' brigade.

Ewell's infantry arrived in Carlisle later in the day and several confederate officers

felt at home. Both General Ewell and

General Iverson had once been posted at the barracks prior to the war, while

they were in the U. S. Army.

Ewell decided to remain at Carlisle while he sent Jenkins'

cavalry and his engineering officer forward to reconnoiter the defenses of

Harrisburg.

On June 28 Jenkins made contact with the enemy at a location

in present day Camp Hill known as Oyster Point where the Oyster family ran a

tavern. (It is the present day intersection of Market and 30th Streets. The skirmish consisted of an exchange of artillery and musket fire which was desultory in nature and lasted for a day. The position was never taken since Jenkins used his time to scout the area. He covered about a four mile front from Oyster Point to Slate Hill.

tavern. (It is the present day intersection of Market and 30th Streets. The skirmish consisted of an exchange of artillery and musket fire which was desultory in nature and lasted for a day. The position was never taken since Jenkins used his time to scout the area. He covered about a four mile front from Oyster Point to Slate Hill.

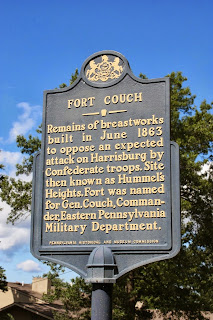

|

| Historical marker for Fort Couch, Lemoyne, PA. |

On June 29 Ewell's division began moving back south by an

order of General Lee. The main body of

the Union army was located in the vicinity of a small town called Gettysburg.

No comments:

Post a Comment